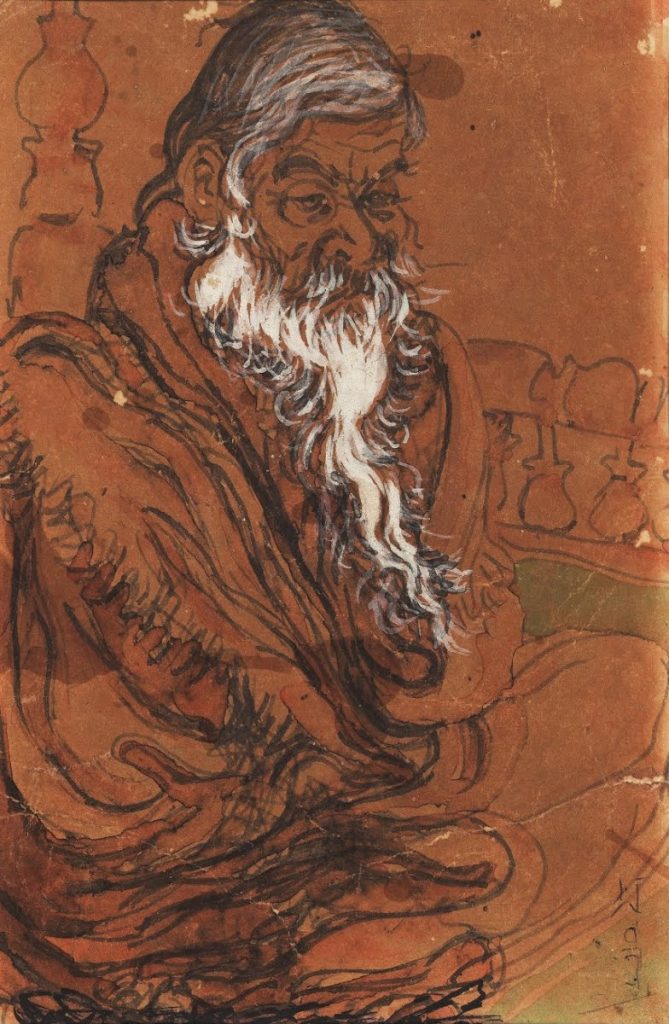

Dealers, gallerists, collectors and auction houses are well aware of this identity issue in Indian contemporary art. Holly Brackenbury, director for Indian art at Sotheby’s London is a regular at events such as the India Art Fair and helps drive sales in London and New York. She says: “The national identity of Indian art is something that has been a concern for some artists since India’s independence. In some cases, the way modern Indian art evolved was by trying to find a voice or an identity. Some looked at taking on aspects of Western art and some looked at returning to traditional forms of Indian art, but using it in a new way to form a language.” [7]

She recognises that the world of the Bengal School in the early 20th century and the post-World War 2 era of the Progressives were different to today’s internet-connected reality with, instant communication and the constant exchange of cultural language. She claims there is now an international cultural language and no longer an emphasis on national identity in Indian art – a claim that can be disputed. Decades after the Bengal School broke from the art constraints of the British Raj, and the Progressives sought to throw off the remnant shackles of British art institutions, it seems the British are again defining and shaping Indian art.

It’s a curious statement when you consider the importance of nationalism and identity in the development of two of India’s greatest art movements. Yet, somehow, Indian art that has no hardcore Indian identity is being lauded by auction houses. The counter-argument could be that it’s those indigenous elements in the works that set them apart in the international market and give them their value.

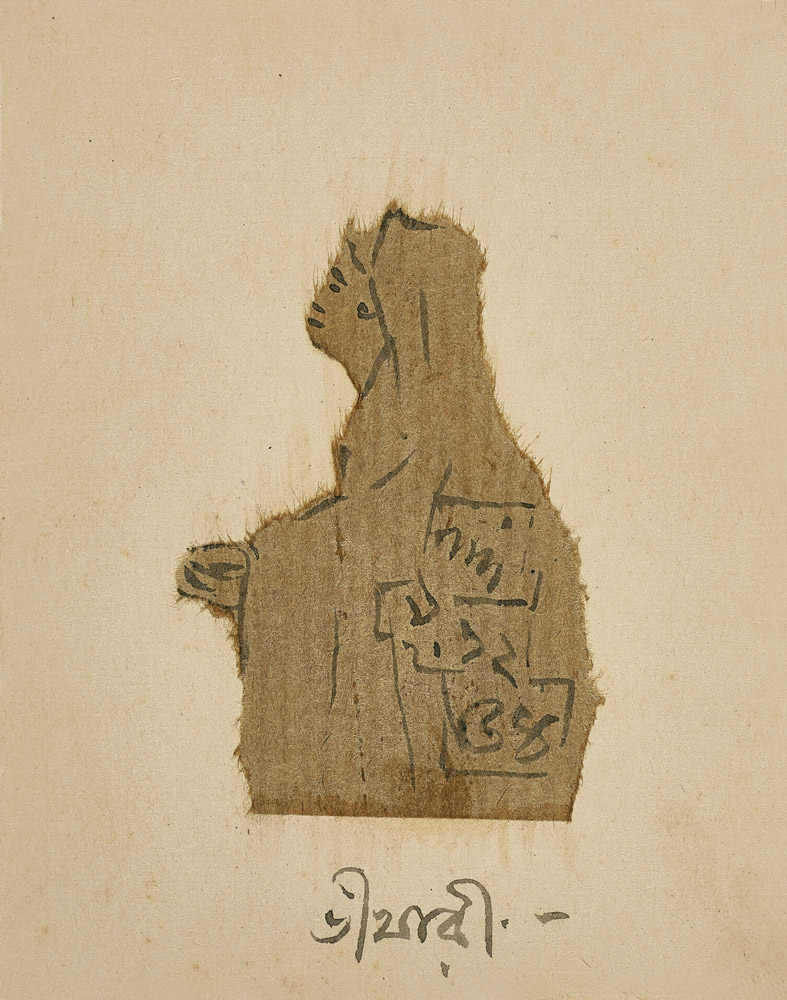

All of this considered, we can conclude that the historical footprint behind the work and master artist status are the best guides to how well they sell at auction, regardless of whether the content is indigenous or Western art-influenced. Visual language will inevitably impact sales but separating the aesthetics into East and West camps does not show the primary driver of sales. This historical footprint, of course, applies chiefly to the best selling movements – phase 1, the Bengal School and phase 2, the Bombay Progressive School.

Sales records show auction houses such as Bonhams and Christie’s prefer the work of these pioneering movements, particularly the Progressives. The founder members and their affiliates are the biggest sellers – the likes of Sayed Haider Raza, M F Hussain, Francis Newton Souza, Vasudeo S. Gaitonde and Tyeb Mehta – all of whose work is clearly rooted in European modernism. Raza, Mehta and Hussain have all broken sales records and V.S Gaitonde’s Untitled (1961) holds the world-record price at $5.5m, this abstract work was sold at the Saffronart Spring Live Auction in March 2021.

Footnotes

[1] India’s nine treasured artists: Can Christie’s create a market for their masterpieces?-

Read more at:

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/personal-finance-news/indias-nine-treasured-artists-can-christies-create-a-market-for-their-masterpieces/articleshow/23220194.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[2] The Salt Satyagraha and Dandi : when Gandhi marched towards freedom (theheritagelab.in)

[3] How Indian art has engaged with the Mahatma – The Hindu

[4] Syed Haider Raza: I’m very attached to Indian culture: Syed Haider Raza – The Economic Times (indiatimes.com)

[5] Maqbool Fida Hussain is described as the ‘Picasso of India’ – Christies, South Asian Modern + Contemporary Art, Live auction 10247, Lot 27, 10 June 2015.

[6] Damien Vesey, specialist head of sale at Christie’s London on the Progressives: “Their works are the cornerstone of any major collection of Indian art.” – author Emma Crichton-Miller, The market is hot for modern Indian art, Apollo Magazine

[7] Holly Brackenbury, director for Indian art, Sotheby’s London: “The national identity of Indian art is something that has been a concern for some artists since India’s independence. In some cases, the way modern Indian art evolved was by trying to find a voice or an identity. Some looked at taking on aspects of Western art and some looked at returning to traditional forms of Indian art, but using it in a new way to form a language.” – author Elīna Zuzāne, Witnessing history of Indian contemporary art, Arterritory

Bibliography

The Legacy of the Progressive Artists Group author Tausif Amin Noor, Sothebys.com.

V.S. Gaitonde’s £3.4m record-breaking painting leads strong South Asian sales season author Kabir Jhala, The Art Newspaper.

10 Things To Know About S.H. Raza, Christies.com.

The Indian art auction market registered strongest sales in a pandemic year author Sneha Bhura, The Week Magazine.

Explained: What VS Gaitonde’s seven top-selling works mean for the Indian art market author Benita Fernando, The Indian Express.

How the Bengal School of Art revolutionised India’s Art Form author Ayesha Ali, Desiblitz.

Rebel, Artist, Pioneer: The Life of Amrita Sher-Gil author Anoushka Khandwala, Elephant.

Amrita Sher-Gil’s Record Spotlights One of Art History’s Most Remarkable Women author Uri Bollag, Mutual Art.

The market is hot for modern Indian art author Emma Crichton-Miller, Apollo Magazine.

Witnessing history of Indian contemporary art author Elīna Zuzāne, Arterritory.