The Victoria and Albert Museum in London exhibited ‘The Fabric of India’ – an exploration of the handmade textile industry of India -in October 2015. This was the first exhibition of its kind to highlight the historical wealth of Indian textiles that withstood colonisations and the post-independence era. Over 200 objects curated by international partners, designers and the V&A’s own collection were displayed for three months and showcased 6000 years of history.[1] Contemporary art spaces hosting non-western art alongside western art has created a new ‘global art’, where curators and museums bring together a varied scope of cultures under a common artistic platform. This attempt at homogeneity has aided in bringing the creativity of the past with the historically forgotten under one roof. Whether the step has been positive or negative is subjective in nature to the beholder. In the larger context of exhibiting Indian textiles to a global audience, museum curators deliver an insight into the significance of the artisan’s skill. Indian history is woven in the transforming imageries of the cloth, and after centuries of imperial struggle and political protest, today’s textile artisans govern these traditional skills and adapt them to suit modern day consumerism.

At the heart of the global response to Indian textiles is Kalamkari art. With a lineage dating back a few thousand years, this art form has evolved throughout the centuries and continues to adapt new designs into its evolutionary history. The art originated from the tradition of story-telling and retelling the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, through Hindu mythological imagery. Representations were created with traditional hand-painting using the ‘kalam’ pen, and adapted temple mural art onto textiles. This flourished in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh in India, and in the 14th century, the holy town of Srikalahasti was a production centre under the patronage of Hindu princely states, deriving the eponymous Srikalahasti style of Kalamkari.

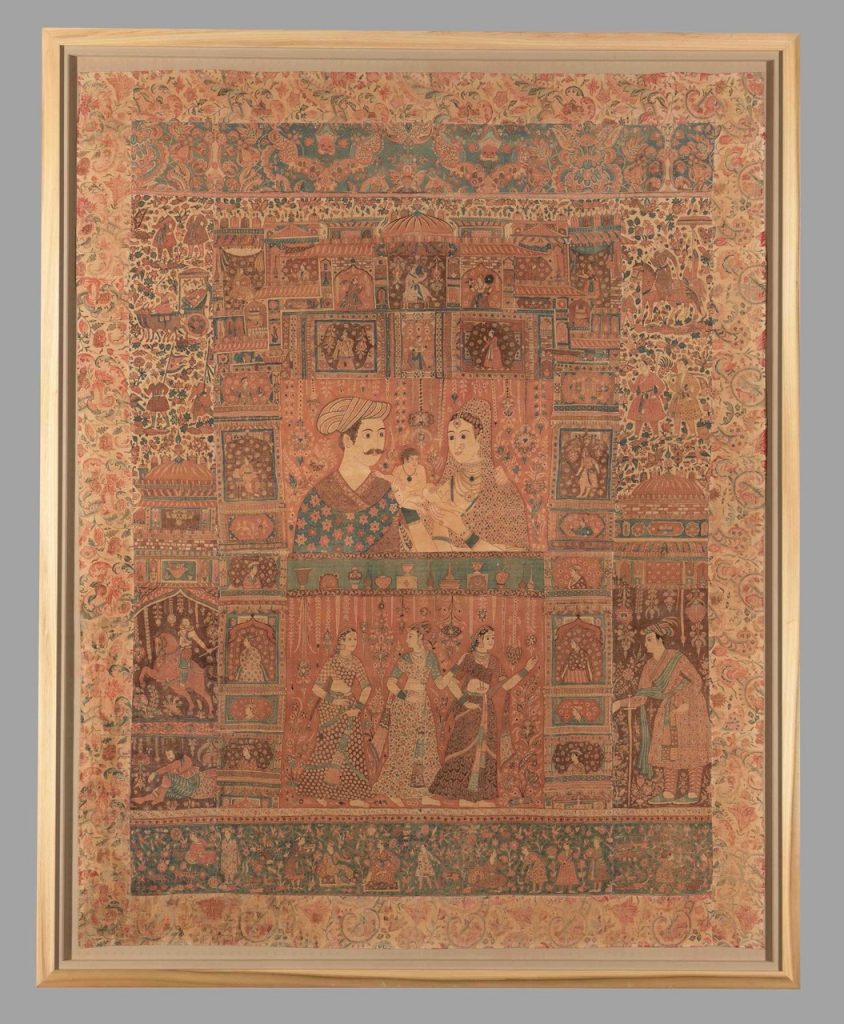

Kalamkari printing is an intensely laborious process involving over 20 stages that begins with cloth being washed in buffalo milk and bleached using myrobalan for the resist. The freehand drawings are done using a kalam with black ink derived from iron and red ink from chay roots, followed by further dyeing in alizarin and starching before fixing the cloth.[1]It is essential to understand the ecological influence in the practice and workmanship of the Kalamkari art tradition, a task greatly enhanced by the sands and waters of the south eastern Coromandel coastline, which sustains the original authenticity of the centuries-old practice. Years of maintaining quality through environmental change is as commendable as the intensive work undertaken in its finish.

Cultural change is impacted by popular receptivity and the patrons that support the art form. The mythological themes in the original Srikalahasti style had figures with embellished clothing and ornaments pertaining to those worn in temple premises. Subsequent Persian invasions of India created parallel forms of artistic representations, and popular patterns such as the ‘Tree of Life’ motif and those inspired by flora and fauna soon replaced mythological imagery. The Golconda Muslim Sultanate that ruled around the early 16th century onwards, based the city of Machilipatnam (or Masulipatnam) as its major centre of production of trade for the Persian, Arab and Far Eastern markets. Block-printing using vegetable dyes was typical of the Machilipatnam style of Kalamkari as it produced repetitive prints and designs that aided mass textile production for international trade. Travelling merchants carried these in exchange for spices from the Far East and to sell further afield in the Persian markets. Adapting textiles over centuries to the needs of international markets exemplifies how artforms influenced foreign cultures while simultaneously being shaped by foreign influences.

‘An art under a ‘modern structure’ can undergo a deviation from its past and its beginnings to conform to the ‘aesthetic sensibilities of a consumer.’[1]It is the market traders who initiate expansion for business purposes to meet production and supply, those who have a larger role to play in the transformation of the art form.

European colonisation spread Kalamkari art towards Europe: the ‘English called it ‘chintz’, the Dutch called it ‘sitz’ and the Portuguese ‘pintado’.[1] This western migration introduced embroidered floral patterns to aesthetically appeal to an entirely new culture of patrons. The Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 in South Kensington was the first instance of recognition that helped secure Kalamkari a global standing. However, now popularised through beddings, furnishings and calicos, with time, all patterned cloths were referred to as ‘chintz’. As an artist’s identity is entwined within the roots of traditional artisan practices, this journey of Kalamkari towards a homogenous identity exemplifies the artisan’s struggle for survival under varying reigning patrons and imperial rulers.

Museums created homogeneity amongst the arts of non-western origins, whilst facilitating collaborations and co-curatorship for artists.[2] Perhaps purists of a tradition would argue that this is problematic as the original essence has been lost over time; however, from a 21st century global village perspective, the ancient practice has been kept alive to this date, and offers new perspectives by bringing long forgotten crafts of beauty out from the shadows and into the present age.

The history of the Kalamkari textile shows the extent that artists have sustained a centuries old practised skill. Financial support remains a crucial long-term strategy for its continuity. Since registering the Kalamkari art of Machilipatnam under protection in 2013, the Indian government has secured the authenticity of the craftwhile NGO’s such as the Vegetable Dye Hand Block Kalamkari Printers’ Welfare Association have safeguarded the wellbeing of the artisans. One such undertaking is ‘DWARAKA’ which aims to bring gender equality within the practice. The artisan now becomes the designer and the entrepreneur, with access to enterprise, creativity and growth, and bestowing pride in art as a profession to future generations. Here is a grassroots example of individuals taking a primary role in the conservation of an industry, and bringing monetary value to an art heritage that has stood the test of time.[1]The socio-economic struggles through European colonial patrons and the waning strength of Muslim rulers is central to the aesthetic value placed on this art. Keeping certain traditions intact becomes a challenge when people are conquered – hence keeping art forms alive is central to a nation’s heritage.

The continuation of traditional arts brings histories to the forefront and aids galleries, auction houses and museums who directly or indirectly support these processes in a global market. Sharing cultural traditions, otherwise trapped beneath the cottage industry’s label, helps to garner new audiences, but more importantly, empowers those who have practiced the tradition for generations, with sustainable growth and economic self-reliance. When museums and similar institutions present traditional indigenous arts they are creating a means to secure financial investment and aid for long-term planning and enterprise. For participants, it has provided an outlet for their story and cultural identity.

Footnotes

- http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/the-fabric-of-india/

- Rajan, A. and Ranjan, M.P. (2007)

- Greenberg, 1960

- Ghosh, S. 2018

- Edwards, E., (2018).

- DWARAKA Development of Weavers and Rural Artisans in Kalamkari Art

- Bibliography

- Buchholz, L. and Wuggenig, U., (2005) ‘Cultural Globalization between Myth and Reality: The case of the Contemporary visual arts’, ART-e-FACT: Strategies of Resistance, Glocalogue Issue 4, Accessed from: http://artefact.mi2.hr/_a04/lang_en/theory_buchholz_en.htm

- DWARAKA Development of Weavers and Rural Artisans in Kalamkari Art [Website] http://www.dwarakaonline.com/index.htm

- Edwards, E., (2018). ‘Addressing colonial narratives in museums’ [Blog], The British Academy: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/blog/addressing-colonial-narratives-museums/

- Fotheringham, A. (2016) ‘Guest Post : Exhibition Designer Gitta Gschwendtner Reflects On a Job Well done’, Asia: The Fabric of India, [News, articles and stories from the V&A blog], Accessed from: https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/fabric-of-india/guest-post-exhibition-designer-gitta-gschwendtner-reflects-on-a-job-well-done-and-takes-a-video

- Ghosh, S. (2018) ‘Retracing Kalamkari’s journey: from classic to a contemporary textile art’, The Chitrolekha Journal on Art and Design, Vol. 2, No. 2, [Themed Issue on “Contemporary Art Practices in Twenty-first Century India”], Accessed from: Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad.DOI:https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/cjad.22.v2n201PDFURL:www.chitrolekha.com/ns/v2n2/v2n201.pdf

- Greenberg,C.(1960), ’Modernist painting’,In Forum Lectures(Voice ofAmerica),Washington,DC, Accessed from Open University: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=882620§ion=2.4

- Rajan, A. and Ranjan, M.P. (2007), Kalamkari – Dye Painted Textiles’, Handmade in India: a geographic encyclopaedia of Indian handicrafts, [Book] National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, India

Source Image file

- Kalamkari Rumalca. 1640 –50,Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession Number: 28.159.3 (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/448214)

- Kalamkari Hanging with Figures in an Architectural Settingca. 1640–50, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession Number: 20.79 (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447118)

- rajaramansundaram, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KALAMKARI_HAND_PAINTED_CLOTH_SRIKALAHASTI_AP_-_panoramio.jpg)

- Kalamkari Hanging Painting ca. 19thC(late)-20thC(early), British Museum, Museum Number: 1991,0327,0.1 (https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1991-0327-0-1)

- Adbh266, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kalamkari_design_-.jpg)